Techniques and materials for thatching

Before I try to draw some provisional conclusions about thatch in Breconshire, I wanted to explore the technical details of thatching.

While at a glance they may all look similar, thatched roofs come in a wide variety of styles and materials and are far from simple in construction. They consist of several distinct elements, each of which might be made using materials and techniques which vary widely from area to area. What follows is a brief summary of a complex subject. For anyone who would like to know more, Eurwyn William’s book The Welsh Cottage is an excellent guide.

To create a thatched roof, a foundation layer must first be laid over the rafters to provide a base for the thatch above. This might be made of wattle, poles or rough branches, or of woven mats or straw rope. On top of this, a layer of ‘underthatch’ is placed. This provides both insulation and something to fix the top layer to and might be made of straw, reed, gorse, bracken, heather or turf.

Above the underthatch, the visible top layer or ‘weathercoat’ is laid. The main function of this is to carry rainwater off the roof, so it must be laid in a manner which helps the water flow easily down to the eaves. It might be made of wheat straw (barley and oat straw being less suitable), rushes or reed-grass (this is not the same as ‘Norfolk reed’, the most common thatching material today, which was not used historically in Wales). The top coat might be ‘combed’ before laying to make it neat and parallel, or wetted to make it stick together better. Unlike the underthatch, which can potentially stay in place for centuries, the upper layer has to be renewed regularly. The better materials might last 20 or even 30 years, but lower quality materials might need renewing after as little as five.

The final, and crucial, element of a thatched roof is the ridge at the top. This is the most difficult to construct because it is most vulnerable to water penetration. It might be made of straw or reed, but turf and clay were also used (sedge, the classic ridge material of eastern England was less common in Wales).

Whatever material the thatch was made of, a variety of techniques were used to secure it. Eurwyn William has summarised the geographical distribution of four main methods:

In western coastal areas, where winds were particularly strong, ‘rope thatch’ used a network of ropes on top of the thatch, weighted with stones, to hold the roof in place.

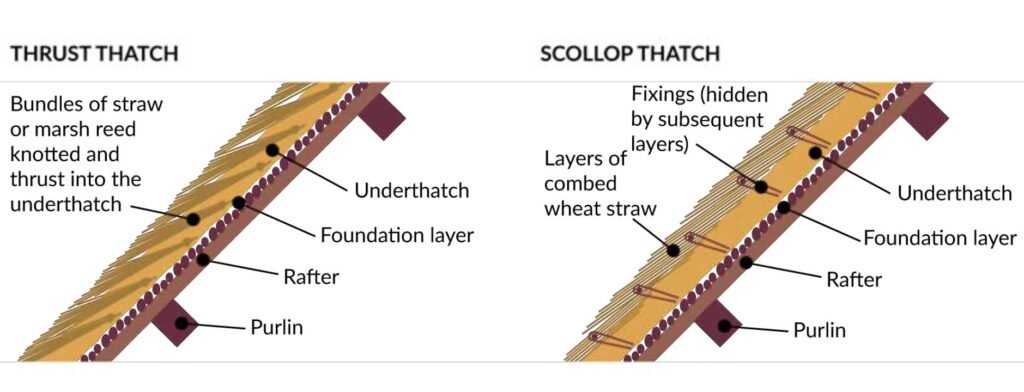

In other western parts of Wales a technique known as ‘thrust thatch’ was used – bundles of material were knotted at one end and ‘thrust’ into the underthatch using a specially shaped tool known as a ‘toibren’.

In the south-east of Wales, and in some border areas further north, a ‘scollop’ thatch method was used – the thatch was secured using wooden spars and pins or ‘scolps’ which would be hidden from view as further layers of thatch were added. This method was also known as ‘Glamorgan thatch’ and that county has the strongest continuous thatching tradition in Wales today. Glamorgan thatch is similar to the ‘combed wheat reed’ thatching tradition of south-west England, which differs substantially in materials and appearance from the ‘longstraw’ and ‘Norfolk reed’ styles which are dominant elsewhere in England.

Cross-section diagram showing both thrust thatch and scollop thatch.

Between the ‘thrust’ and ‘scollop’ thatch areas, William identified a ‘mixed’ thatch area in which the ‘thrust’ thatch method was used but additionally secured with wooden ‘scollops’.

Distribution of the four main thatching techniques inWales, after Eurwyn William, The Welsh Cottage, p144, with outline of Breconshire added

William’s map suggests that Breconshire was at the meeting point of three traditions, the south of the county falling within the ‘scollop’ thatch tradition but the north being in the ‘thrust’ and ‘mixed’ areas. He illustrates a ‘toibren’ associated with those latter traditions which came from Breconshire, but describes no examples of thatch from the country.

As well as the techniques and materials used in thatching, we also need to consider who was doing the thatching and how the materials were obtained. Details about this are limited, but we do have some information from agricultural leases. In general, it was considered the responsibility of the landlord to provide buildings and of the tenant to keep them in repair, which would include re-thatching. But Penpont leases show a variety of arrangements being used in practice, especially at the start of a tenancy, for example:

At Pantycelyn, Crickadarn, in 1734 the landlord was to provide masons and carpenters work for repairs, but the tenant was to haul the timber, stones etc and to do the thatching work.

In a lease of 1741, the new tenant of Cefn-y-parc farm, Llanspyddid was to ‘thatch all the houses that are to be thatched’ himself, although he was allowed 30 shillings towards the cost.

Ty-Hir, Crickadarn, 1757, the landlord is to build a house and a beasthouse and put all the other buildings in repair. The tenant is to haul ‘stone, earth, water, mortar and all other necessaryes’, to attend the masons and to thatch the buildings, and to have an allowance of 42 shillings against repairs.

In 1817, the tenant of Upper Wern Figyn in Trallong was allowed a guinea against rent for hauling fern (ie bracken) for ‘nine lights of thatching’ (a ‘light’ is probably the same as a ‘bay’).

In 1825, Thomas Rees took on a cottage in Defynnog which had formerly belonged to Mary Evans – he was to mend the thatch himself, being allowed a guinea against the cost and timber for the roof.

Usually the landlord was to provide timber, stone and mortar, but I have only found one reference to the landlord supplying thatching materials. The 1734 Crickadarn lease specifies that the landlord is to provide broom for thatching, but the arrangement was to be ‘during this year only’ which suggests it was regarded as exceptional.

If the landlord was responsible for providing the skilled work of masons and carpenters, the tenant was to provide the less skilled labour of hauling materials and ‘attending the masons’ (sometimes feeding them as well). In the Penpont documents I have not found ‘thatchers’ listed alongside masons and carpenters. Where mentioned, thatching is usually the tenant’s responsibility. Whether the tenant was expected to do this work personally or to employ a thatcher is not specified, but it seems likely that many farmers and agricultural labourers would have had at needed at least some thatching skills in order to thatch the ricks used to store hay or corn crops.

In the next instalment, I will try to reach some initial conclusions about thatch in Breconshire.