A thatched cottage in Breconshire

I suspect that most people, if asked what the traditional roofing material of Breconshire is,

would answer ‘Welsh slate’. It is certainly the commonest material on old buildings today,

although it comes from quarries on the other side of the country. A more truly local material

is ‘stone slate’, ‘stone tile’ or ‘tilestone’ quarried from seams of sandstone that could be

split into slabs which, although thicker and heavier than true slate, were suitable for roofing.

Almost prohibitively expensive today, some fine examples can still be seen, such as the roof

at Tretower Court.

But I wonder how many people would think of thatched roofs as a feature of this county? I’d

love to be corrected but I’m not aware of a single historic thatched building standing in

Breconshire today. And yet, in my work on the Penpont estate, I keep on coming across

documents which refer to thatch. For example, the tenant’s responsibility to thatch their

buildings is specifically mentioned in leases for Pantycelyn and Tir-Hir farms in Crickadarn in

1734 and 1757 respectively. There are other references to thatch on farms and cottages in

Ystradfellte, Trallong, Llanspyddid, Penpont and Defynog parishes.

Perhaps most interesting among these documents is an architect’s plan and elevation,

drawn in 1891, of a one-roomed thatched cottage in Trallong. It records what I suspect by

then was one of just a handful of thatched buildings surviving in Breconshire. In fact,

‘surviving’ is perhaps too strong a word – the cottage was ruinous and the drawing shows

how it would look if restored. However, the level of detail suggests that enough survived for

the architect and surveyor, William Williams of Brecon, to give a fairly accurate impression

of how it had looked.

Plan and elevation of Cwm Nant Cottage, William Williams 1891 © Private Collection

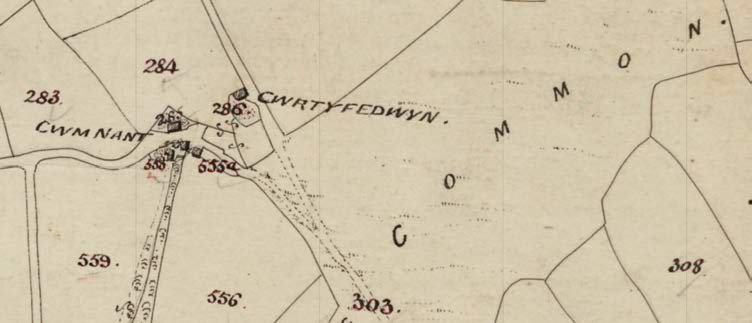

The cottage lay in the small valley known as ‘Cwm Nant’ immediately south-east of where

the road to Pentre Felin crosses the stream (SN 949 302). It was one of a group of three

cottages and one other building shown clustered around this crossing on the tithe map of

1840. It was named simply ‘Cwm Nant Cottage’ and its tenant was Watkin Walters.

Part of Trallong Common from the tithe map of 1840. Cwm Nant Cottage was number 555a. © Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – The National Library of Wales

https://places.library.wales/browse/51.961/-3.527/17?page=1&alt=&alt=&leaflet-base-layers_70=on

These buildings were among several cottages and smallholdings on or around the edges or

Trallong Common (a lowland common in the west of the parish, not to be confused with the

open mountain land on the ridge to the north). Most of these dwellings had been enclosed

from common land and so were considered the property of the Lord of the Manor, the

Bishop of St David’s.

Overall, about half of these buildings survive today, generally those within larger enclosures,

but our cottage and its immediate neighbours have vanished, although nearby Cwrtyfedwyn

remains. (A substantial area of the Common is still open land today. It is interesting to

contrast this with the smaller lowland common at Cyffredin, Llangynidr described by John

Gibbs in Brycheiniog Vol. 52, where even by 1840 piecemeal enclosure has been so

extensive that the common itself has all but disappeared.)

By 1733, the Bishop had let these cottages to the Penpont estate, owners of much of the

surrounding land, who sub-let them to more modest tenants. In 1891, when the lease was

due for renewal, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners offered Penry Boleyn Williams (1838-

1893), then owner of Penpont, the chance to buy the freehold for £581 11s. They also

arranged for William Williams to survey the properties, detailing the work required to put

good the ‘dilapidations’ to the buildings and fences. The estimated cost of this work came to

£69 13s 8d, of which the bulk, £46 10s, was for the re-building of the ruinous Cwm Nant

Cottage.

It may be that these ‘dilapidations’ were really a bargaining point to encourage the Penpont

estate to buy the cottages outright and so avoid this charge. In the background, a deal was

also being negotiated for the estate to give some land in Trallong village for a new vicarage.

However, Penry Boleyn Williams died before these arrangements were completed and his

successor, his sister Anna Maria Williams (1835-1932), declined to purchase and paid the

charge for ‘dilapidations’. (She did eventually purchase some of the properties around 1922,

although at a rather lower cost.)

The cottage never was rebuilt. Probably nobody seriously thought it would be, especially

not in its original form. The purpose of the survey was to establish a notional cost of

restoration to be paid by the outgoing leaseholder, but in doing so it has left us an

interesting and relatively detailed record of a building of such low status that it would have

passed under the radar of most architectural historians of the time. In its day, this would

have been one example among thousands across Wales of a simple edge-of-common

building – a building similar in spirit, if not in strict reality, to the ‘ty unnos’ (one-night

house) tradition. These were small and basic cottages with no architect, perhaps

constructed largely by the resident with the help of friends and family. Many of these have

simply disappeared – those which survive have been rebuilt in a more substantial manner.

Of the other Trallong Common cottages surveyed in 1891, all had slate roofs by then.

The room in Cwm Nant Cottage was a respectable size: 16 ft 6 in by 14 ft internally. That’s

larger than the living rooms in many modern developments. But it was the only room, also

serving as kitchen, bedroom and everything else. The stone walls were 2 ft thick and 7 ft 6 in

high to the ‘square’ (i.e. the eaves). There was one door and two small windows, and a

fireplace with a grate, ‘stone hobs’ and a round oven built into the wall. The floor was

apparently ‘concrete’ but in need of repair. There is no mention of any upper story – not

even a ladder or crog-loft is described.

There is a fairly detailed specification for the roof. It was to be re-built with ‘one rough

principal rafter from the saw’, joined by a ‘spanbeam’ (i.e. tie beam), which would support

four purlins and a ridge piece. These in turn would support common rafters ‘in the rough of

fir poles or cleft oak’ set 12 inches apart. Above these was to be laid a ‘rough bedding of

Fern or brush wood’ on top of which ‘a good coating of Straw’ was to be ‘properly laid, and

secured to the wood work’.

Finding this description made me wonder what other evidence there might be for thatched

buildings in Breconshire. To think that in the past one might have seen thatched roofs in this

part of Wales I find intriguing – something which would alter my mental picture of past life

in Breconshire significantly. To find out more, I undertook an online search for other images

of thatched buildings, the results of which I will give in the next instalment.